What Does it Cost to Change the World? from WikiLeaks on Vimeo.

What Does it Cost to Change the World? from WikiLeaks on Vimeo.

Via Postal Mail - You can post a donation via good old fashion postal mail to: WikiLeaks (or any suitable name likely to avoid interception in your country), BOX 4080, Australia Post Office - University of Melbourne Branch, Victoria 3052, AustraliaMonday, April 08, 2019

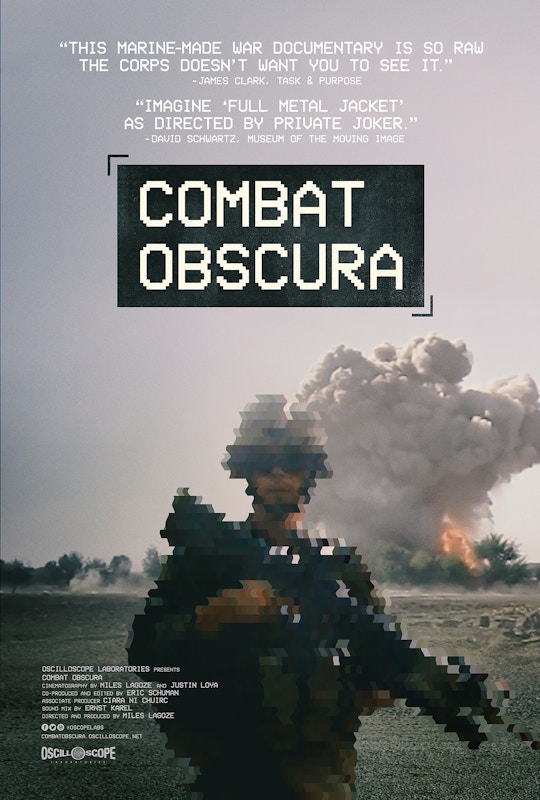

Combat Obscura - from The Intercept

"I want there to be some accountability. I don’t want people just to look at the soldiers and Marines as hapless victims that were sent out there, and it was just the big politicians that are responsible. No. I think the soldiers are responsible, the politicians are responsible, but also the American people are complicit. Our tax money funded the war. It’s not just the soldiers and the politicians. It’s the everyday citizens. We’re all responsible because we didn’t really give a shit. We didn’t notice it. We didn’t pay attention."

https://theintercept.com/2019/04/07/combat-obscura-afghanistan-war-documentary/?fbclid=IwAR0SgfYs4gdS-hFrXrfhFSFP5ke7gIV1zCWSpm40UDLdacPH6xEsr03Bmz8

A Veteran’s War Movie Sheds Damning Light on How the Marines Fight in Afghanistan

“Combat Obscura” begins

with explosions. Half a second later, a great column of smoke

materializes in the distance, quickly doubling and then tripling in

size. But most frightening of all is what’s happening behind the camera.

A man yells, in English, as the cloud grows past the top of the frame.

“Holy shit,” he says. “That’s the wrong building!” Another explosion

sounds, and a fireball billows. “Holy shit!” he yells again; he is

gleeful, fascinated now. “Yeah, boy!” he shouts.

In “Combat Obscura,” a new documentary set in Afghanistan, Marines don’t do what they normally do in American-made documentaries about war – they don’t echo narratives of God and country, kill bad guys, and win hearts and minds. In “Combat Obscura,” Marines shoot guns and patrol, but they also insult women, shake their weapons at children, die needlessly and with little dignity, murder innocent people and cover it up. At one point in the film, a Marine points his gun at children passing by on donkeys. “Where’s the fucking Taliban? Where’s the fucking Taliban?” he screams in their faces. They look back in fear and incomprehension. The Marine hands one of the boys a chocolate bar, but it does not feel like a kindness.

Director Miles Lagoze, 29, joined the Marines just after graduating from high school and quickly deployed to Afghanistan. His job in the Corps was what’s known as combat camera, a role that entails capturing footage of Marines for operational use on the battlefield and for PR back home. “Combat Obscura,” which was released March 15 with Oscilloscope Laboratories, is almost entirely comprised of footage Lagoze and another combat cameraperson, Justin Loya, shot for the Corps. The film amounts to a deft 110-minute condemnation of the behavior of U.S. troops and an excruciating lament for the needless loss of life caused by the American war in Afghanistan. The Intercept talked to Lagoze about why he made the documentary, the legal process that preceded the film’s release, and his feelings about having taken part in the war. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to enlist in the Marines right out of high school, when you were 18?

I think I was just kind of directionless. I had this preconceived notion that going to war would give me a perspective on life that I wouldn’t get somewhere else. And I always wanted to cover the war as a journalist. I wanted to go to grad school and stuff. I was a huge movie buff when I was a kid, and I saw “Full Metal Jacket” a bunch of times, and I was like, “Oh, you can just join the Marine Corps, they’ll give you a camera, and you just film for the military.'”

I think the military offered that easy, very direct path to another place. A lot of people think the military’s just these patriotic kids — guys that just want to serve their country. But it’s a lot of kids that are just on the fringe.

Where were you deployed and when?

We were in the Sangin-Kajaki area of Afghanistan in 2011. And we didn’t know it at the time, because they don’t really tell you anything when you’re going to these places, but there’s a dam in Kajacki. It basically powers the whole Helmand province with electricity. It was missing a third turbine. It was heavily occupied by the Taliban. We had to clear a route there to fix the dam. The dam is still broken. It’s sort of a metaphor for the whole war, I guess.

Combat camera is sort of like a PR tool for the military. In 2011, when I was there, we were supposed to be transitioning out of Afghanistan and handing it over to the Afghan army, the Afghan people. My job was to document those images: Marines working with the Afghan army, giving candy to kids — hearts and minds type of stuff. The big three no-nos were no cursing, no shots of guys smoking cigarettes, and they have to be in full gear. And then no casualties. That was a big one, not too much bloodshed. Because it was supposed to look like it was over, we were pulling out. This was eight years ago. And we’re still there.

What was your aim in making this documentary?

It’s supposed to be a poem. We want to give people the experience of the war, the uncertainty of it, and the paradoxes. And it’s sort of a meditation on what it’s like to be a solider, how absurd this war is — there wasn’t even a definition of what the outcome was going to be, what winning would even look like, or anything, really. And just the waste of life.

That’s really all I can do. That’s all I can hope for. I don’t want people to come away with some kind of answer to the conflict. I think when you see civilian documentaries about it, you sort of get that kind of closure, in some sense, like, okay, it’s all about camaraderie, or it’s all about the guys and being out there with one another. And oh man, they’re going to be so fucked up when they come back. No. I really want to unsettle people and put them in that moment.

That makes me think of a narrative choice that you made, which was not to do any kind of “Where are they now?” interviews, and not have voiceovers. Why didn’t you use devices like that?

Well, people always want that. I’ll tell you: A lot of [the Marines in the film] are in jail. Some of them are doing okay, and some of them are not. And some of them are dead. Some of them killed themselves.

But this whole myth of the trauma hero of American war narratives — I didn’t want to do that. Every American war narrative tends to revolve around, Johnny’s got this naive notion of war, and he goes over and it’s not what he expected, and it’s total chaos and horror, and then he comes back, and he has no way to express what it was like. When I first set out to make the film, I did interviews with a lot of the guys that were in the film, in the present. When I started to get rid of that, I think that’s when it became more honest.

I want people to question them. Not just sympathize, but question, and look at who we were sending to fight these wars. I mean, it’s an all-volunteer military. It’s not like we were drafted. We all grew up watching “Full Metal Jacket,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Platoon.” These are anti-war films that I think had the reverse effect on a lot of us, because we have this whole reified notion of war and trauma, and going to war, and that you’re going to learn something by going to combat. And it takes away from the actual reasons we’re over there.

What was it like when you would bring the camera out when Marines were smoking weed, for example? Was there resistance to it?

A lot of the guys in the film had been on multiple deployments, and they were getting out of the military. They were done with the Marine Corps; they hated the Marine Corps. [Some] of them had gotten DUIs and gotten into trouble. They were sick of it. And they were getting out in a few months, so some of them didn’t care at all and they wanted me to film.

And then other guys were like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, what are you doing?” But as a Marine, you can just be like, “Oh, fuck you,” and just do it. And you can see some of the guys in the film — they want to rap, they want to be on camera. I wasn’t going to show it to the command, so they weren’t worried about that.

Another theme in the documentary is masculinity. Can you talk a little bit about that, and if your perception of it has changed since you were in Afghanistan?

It would actually be interesting to go see what the Marine Corps is like now that women are in combat roles, because when we were there, they weren’t allowed in the infantry. They could serve other jobs, but they couldn’t be in active combat. So the Marine Corps that I knew was extremely toxic. Even boot camp. The drill instructors would literally tell you that your girlfriends are whores and they’re cheating on you as we speak. So they instilled this innate hatred of women from the beginning.

It’s hard to imagine what fighting a war would look like if there wasn’t toxic masculinity involved in the training process. Because you’re being trained to kill people, and to not be thoughtful about those things, and to basically be excited to go to war.

Tell me about your decision to portray the shooting of a Marine, Jacob Levy. Was that a complicated one for you?

Yeah, definitely. I felt guilty for a long time for just filming it.

Instead of intervening?

Or just maybe not recording it. Just being like, “You know what, I’m not even going to film this. People don’t need to see this.”

There’s filming it, and then there’s showing it. Filming it, okay. You were there, this was my job to film, sure, whatever. But then showing that and not sanitizing it at all, and sort of emphasizing it almost —I think it is the longest sequence in the film — was definitely a tough decision.

I talked to his mom. All the guys that were there go to see her every year on his birthday, and on the day that he died, too, so she has this cult of veterans. She’s like a super Gold Star Mom, and so getting her permission was really important, but it’s always going to feel kind of exploitative.

Ultimately, you think of all the documentaries that have come out about Afghanistan or Iraq, they tend to show a lot of dead Iraqis, dead Taliban, dead Afghan women, children. It’s like there’s no problem to show that, but then when there’s a dead U.S. soldier, that’s off limits. We didn’t want to value one life over the other.

So you got permission from Levy’s mother to put that in the film. Did you have to get releases from everybody who appeared in the film?

Not everyone. I was moving around so much to each platoon that I didn’t know everyone. But the guys smoking weed, I wanted to make sure they didn’t have government jobs now, which would get them in trouble. The statute of limitations has passed so it’s not like they could be retroactively dishonorably discharged if they’d been honorably discharged. I talked to lawyers about that before anything.

There wasn’t really anything else that was illegal. The dead civilian — they were cleared to shoot that guy, even though he was unarmed. So that tells you a lot about what goes into the rules of engagement in Afghanistan.

The guy chasing the kids with the pistol, he has a wife and kids, so I wanted to be like, “Are you going to want them to see this?” And he was like, “Yeah, man.” A lot of them are at a point where they want to be judged to a certain degree. Stop saying, “Thank you for your service.” It doesn’t make sense. It’s totally absurd.

Maybe you’re thinking that the military’s this really organized body that keeps track of everything, and it’s not. It’s just as disorganized as any other business or bureaucracy or government institution. Everyone had cameras, so they weren’t looking through other people’s cameras. They were mainly looking for guys bringing drugs back, bringing weapons like AK-47s that they had found from dead Taliban. There was one guy who tried to bring a grenade on the plane back, which is obviously not a good idea for a lot of reasons. So they weren’t like, “Alright, everybody take out their cameras now.”

If you had been through that experience, you’d almost died filming a lot of the stuff, you’d want to keep it. It was a diary of our experience, and I wasn’t just going to throw that away.

Did you have a legal process as you got closer to releasing the film?

I reached out to a lot of different people along the way. One of them was Phil Klay, who wrote “Redeployment.” He’s a National Book Award winner, and he was public affairs in the Marine Corps around the same time that I was there. And I was like, “I want to get this released somehow, but I don’t want to deal with the Marine Corps itself, because I know that they would just flip out.” So he told me about the review process at the Pentagon. And I sent it to the Pentagon, they cleared it, it was unclassified.

But then the Marine Corps heard about it. The Pentagon sent it to the Marine Corps. The [Naval Criminal Investigative Service] was calling me, and different people at the Marine Corps. The Marine Corps Entertainment [Media] Liaison Office wanted to meet with me. And that’s when I was like, I need to get a lawyer or something.

[The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University] kind of took me in pro bono. Without them, I’d be in a whole bunch of legal trouble. And they got another legal firm involved called Jenner & Block that does a lot of pro bono stuff. Once I had them in my corner, I think just their presence had an effect on the Marine Corps. Right now, they’ve publicly stated that they’re not pursuing legal action.

You mentioned your guilt about filming a fellow Marine being shot. Do you feel guilt about participating in this war? And if so, how have you dealt with that?

Absolutely. The veterans that are actually honestly reflecting about it [have] a lot of conflicted feelings. On the one hand, you went there and you made it out alive, and it’s such a transformative experience at such a young age that it’s hard to disconnect from the emotional experience you had there and the friends that you lost, and the buddies who left body parts there. It’s hard to disconnect from that and go, “Our presence there was not just a waste, but my presence there probably could have made things worse.” I know a lot of vets who are unwilling to come to that because while they were out there, they truly felt that they were helping Afghans, because they were fighting against the Taliban.

But you have to think about it: While we were there, we created an almost uninhabitable environment for the Afghan civilians. Because before we were there, they were oppressed by the Taliban. While we were there, they were caught in the middle between two oppressive forces. And how many times did we bomb their houses? How many times did we mistakenly kill innocent people?

In “Combat Obscura,” a new documentary set in Afghanistan, Marines don’t do what they normally do in American-made documentaries about war – they don’t echo narratives of God and country, kill bad guys, and win hearts and minds. In “Combat Obscura,” Marines shoot guns and patrol, but they also insult women, shake their weapons at children, die needlessly and with little dignity, murder innocent people and cover it up. At one point in the film, a Marine points his gun at children passing by on donkeys. “Where’s the fucking Taliban? Where’s the fucking Taliban?” he screams in their faces. They look back in fear and incomprehension. The Marine hands one of the boys a chocolate bar, but it does not feel like a kindness.

Director Miles Lagoze, 29, joined the Marines just after graduating from high school and quickly deployed to Afghanistan. His job in the Corps was what’s known as combat camera, a role that entails capturing footage of Marines for operational use on the battlefield and for PR back home. “Combat Obscura,” which was released March 15 with Oscilloscope Laboratories, is almost entirely comprised of footage Lagoze and another combat cameraperson, Justin Loya, shot for the Corps. The film amounts to a deft 110-minute condemnation of the behavior of U.S. troops and an excruciating lament for the needless loss of life caused by the American war in Afghanistan. The Intercept talked to Lagoze about why he made the documentary, the legal process that preceded the film’s release, and his feelings about having taken part in the war. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What made you decide to enlist in the Marines right out of high school, when you were 18?

I think I was just kind of directionless. I had this preconceived notion that going to war would give me a perspective on life that I wouldn’t get somewhere else. And I always wanted to cover the war as a journalist. I wanted to go to grad school and stuff. I was a huge movie buff when I was a kid, and I saw “Full Metal Jacket” a bunch of times, and I was like, “Oh, you can just join the Marine Corps, they’ll give you a camera, and you just film for the military.'”

I think the military offered that easy, very direct path to another place. A lot of people think the military’s just these patriotic kids — guys that just want to serve their country. But it’s a lot of kids that are just on the fringe.

Where were you deployed and when?

We were in the Sangin-Kajaki area of Afghanistan in 2011. And we didn’t know it at the time, because they don’t really tell you anything when you’re going to these places, but there’s a dam in Kajacki. It basically powers the whole Helmand province with electricity. It was missing a third turbine. It was heavily occupied by the Taliban. We had to clear a route there to fix the dam. The dam is still broken. It’s sort of a metaphor for the whole war, I guess.

Combat camera is sort of like a PR tool for the military. In 2011, when I was there, we were supposed to be transitioning out of Afghanistan and handing it over to the Afghan army, the Afghan people. My job was to document those images: Marines working with the Afghan army, giving candy to kids — hearts and minds type of stuff. The big three no-nos were no cursing, no shots of guys smoking cigarettes, and they have to be in full gear. And then no casualties. That was a big one, not too much bloodshed. Because it was supposed to look like it was over, we were pulling out. This was eight years ago. And we’re still there.

What was your aim in making this documentary?

It’s supposed to be a poem. We want to give people the experience of the war, the uncertainty of it, and the paradoxes. And it’s sort of a meditation on what it’s like to be a solider, how absurd this war is — there wasn’t even a definition of what the outcome was going to be, what winning would even look like, or anything, really. And just the waste of life.

That’s really all I can do. That’s all I can hope for. I don’t want people to come away with some kind of answer to the conflict. I think when you see civilian documentaries about it, you sort of get that kind of closure, in some sense, like, okay, it’s all about camaraderie, or it’s all about the guys and being out there with one another. And oh man, they’re going to be so fucked up when they come back. No. I really want to unsettle people and put them in that moment.

That makes me think of a narrative choice that you made, which was not to do any kind of “Where are they now?” interviews, and not have voiceovers. Why didn’t you use devices like that?

Well, people always want that. I’ll tell you: A lot of [the Marines in the film] are in jail. Some of them are doing okay, and some of them are not. And some of them are dead. Some of them killed themselves.

But this whole myth of the trauma hero of American war narratives — I didn’t want to do that. Every American war narrative tends to revolve around, Johnny’s got this naive notion of war, and he goes over and it’s not what he expected, and it’s total chaos and horror, and then he comes back, and he has no way to express what it was like. When I first set out to make the film, I did interviews with a lot of the guys that were in the film, in the present. When I started to get rid of that, I think that’s when it became more honest.

I want people to question them. Not just sympathize, but question, and look at who we were sending to fight these wars. I mean, it’s an all-volunteer military. It’s not like we were drafted. We all grew up watching “Full Metal Jacket,” “Apocalypse Now,” “Platoon.” These are anti-war films that I think had the reverse effect on a lot of us, because we have this whole reified notion of war and trauma, and going to war, and that you’re going to learn something by going to combat. And it takes away from the actual reasons we’re over there.

What was it like when you would bring the camera out when Marines were smoking weed, for example? Was there resistance to it?

A lot of the guys in the film had been on multiple deployments, and they were getting out of the military. They were done with the Marine Corps; they hated the Marine Corps. [Some] of them had gotten DUIs and gotten into trouble. They were sick of it. And they were getting out in a few months, so some of them didn’t care at all and they wanted me to film.

And then other guys were like, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, what are you doing?” But as a Marine, you can just be like, “Oh, fuck you,” and just do it. And you can see some of the guys in the film — they want to rap, they want to be on camera. I wasn’t going to show it to the command, so they weren’t worried about that.

Another theme in the documentary is masculinity. Can you talk a little bit about that, and if your perception of it has changed since you were in Afghanistan?

It would actually be interesting to go see what the Marine Corps is like now that women are in combat roles, because when we were there, they weren’t allowed in the infantry. They could serve other jobs, but they couldn’t be in active combat. So the Marine Corps that I knew was extremely toxic. Even boot camp. The drill instructors would literally tell you that your girlfriends are whores and they’re cheating on you as we speak. So they instilled this innate hatred of women from the beginning.

It’s hard to imagine what fighting a war would look like if there wasn’t toxic masculinity involved in the training process. Because you’re being trained to kill people, and to not be thoughtful about those things, and to basically be excited to go to war.

Tell me about your decision to portray the shooting of a Marine, Jacob Levy. Was that a complicated one for you?

Yeah, definitely. I felt guilty for a long time for just filming it.

Instead of intervening?

Or just maybe not recording it. Just being like, “You know what, I’m not even going to film this. People don’t need to see this.”

There’s filming it, and then there’s showing it. Filming it, okay. You were there, this was my job to film, sure, whatever. But then showing that and not sanitizing it at all, and sort of emphasizing it almost —I think it is the longest sequence in the film — was definitely a tough decision.

I talked to his mom. All the guys that were there go to see her every year on his birthday, and on the day that he died, too, so she has this cult of veterans. She’s like a super Gold Star Mom, and so getting her permission was really important, but it’s always going to feel kind of exploitative.

Ultimately, you think of all the documentaries that have come out about Afghanistan or Iraq, they tend to show a lot of dead Iraqis, dead Taliban, dead Afghan women, children. It’s like there’s no problem to show that, but then when there’s a dead U.S. soldier, that’s off limits. We didn’t want to value one life over the other.

So you got permission from Levy’s mother to put that in the film. Did you have to get releases from everybody who appeared in the film?

Not everyone. I was moving around so much to each platoon that I didn’t know everyone. But the guys smoking weed, I wanted to make sure they didn’t have government jobs now, which would get them in trouble. The statute of limitations has passed so it’s not like they could be retroactively dishonorably discharged if they’d been honorably discharged. I talked to lawyers about that before anything.

There wasn’t really anything else that was illegal. The dead civilian — they were cleared to shoot that guy, even though he was unarmed. So that tells you a lot about what goes into the rules of engagement in Afghanistan.

The guy chasing the kids with the pistol, he has a wife and kids, so I wanted to be like, “Are you going to want them to see this?” And he was like, “Yeah, man.” A lot of them are at a point where they want to be judged to a certain degree. Stop saying, “Thank you for your service.” It doesn’t make sense. It’s totally absurd.

“Combat Obscura” trailer Video: Courtesy of Oscilloscope Laboratories

How did you get the footage home? Maybe you’re thinking that the military’s this really organized body that keeps track of everything, and it’s not. It’s just as disorganized as any other business or bureaucracy or government institution. Everyone had cameras, so they weren’t looking through other people’s cameras. They were mainly looking for guys bringing drugs back, bringing weapons like AK-47s that they had found from dead Taliban. There was one guy who tried to bring a grenade on the plane back, which is obviously not a good idea for a lot of reasons. So they weren’t like, “Alright, everybody take out their cameras now.”

If you had been through that experience, you’d almost died filming a lot of the stuff, you’d want to keep it. It was a diary of our experience, and I wasn’t just going to throw that away.

Did you have a legal process as you got closer to releasing the film?

I reached out to a lot of different people along the way. One of them was Phil Klay, who wrote “Redeployment.” He’s a National Book Award winner, and he was public affairs in the Marine Corps around the same time that I was there. And I was like, “I want to get this released somehow, but I don’t want to deal with the Marine Corps itself, because I know that they would just flip out.” So he told me about the review process at the Pentagon. And I sent it to the Pentagon, they cleared it, it was unclassified.

But then the Marine Corps heard about it. The Pentagon sent it to the Marine Corps. The [Naval Criminal Investigative Service] was calling me, and different people at the Marine Corps. The Marine Corps Entertainment [Media] Liaison Office wanted to meet with me. And that’s when I was like, I need to get a lawyer or something.

[The Knight First Amendment Institute at Columbia University] kind of took me in pro bono. Without them, I’d be in a whole bunch of legal trouble. And they got another legal firm involved called Jenner & Block that does a lot of pro bono stuff. Once I had them in my corner, I think just their presence had an effect on the Marine Corps. Right now, they’ve publicly stated that they’re not pursuing legal action.

You mentioned your guilt about filming a fellow Marine being shot. Do you feel guilt about participating in this war? And if so, how have you dealt with that?

Absolutely. The veterans that are actually honestly reflecting about it [have] a lot of conflicted feelings. On the one hand, you went there and you made it out alive, and it’s such a transformative experience at such a young age that it’s hard to disconnect from the emotional experience you had there and the friends that you lost, and the buddies who left body parts there. It’s hard to disconnect from that and go, “Our presence there was not just a waste, but my presence there probably could have made things worse.” I know a lot of vets who are unwilling to come to that because while they were out there, they truly felt that they were helping Afghans, because they were fighting against the Taliban.

But you have to think about it: While we were there, we created an almost uninhabitable environment for the Afghan civilians. Because before we were there, they were oppressed by the Taliban. While we were there, they were caught in the middle between two oppressive forces. And how many times did we bomb their houses? How many times did we mistakenly kill innocent people?

I can find myself debating with someone whether we should stay in or

leave Afghanistan. The Afghan army has lost more soldiers the past two

years than we did the entire time we’ve been there. They’re getting

absolutely massacred by the Taliban. And these guys have lost their

whole families to this conflict. This is going to haunt them forever —

they’ve paid the ultimate sacrifice. Not U.S. troops. The Afghans

themselves have lost more than we have by a landslide.

And some of them don’t want us to leave, because if we leave, then they’re done. Because they don’t want the Taliban to win, to go back to what it was before we were there. But there are civilians there that are like, “What are we going to do? A perpetual standoff? A conflict that’s never going to end?” And they’re just caught in the middle.

The personal aspects of the film where you can hear me, or where I’m asking questions, or where I’m filming in a certain way — we left that stuff in the film because of my responsibility and the role that I played and the guilt that I feel about it. I’ve been dealing with it by making this movie.

I want there to be some accountability. I don’t want people just to look at the soldiers and Marines as hapless victims that were sent out there, and it was just the big politicians that are responsible. No. I think the soldiers are responsible, the politicians are responsible, but also the American people are complicit. Our tax money funded the war. It’s not just the soldiers and the politicians. It’s the everyday citizens. We’re all responsible because we didn’t really give a shit. We didn’t notice it. We didn’t pay attention.

And some of them don’t want us to leave, because if we leave, then they’re done. Because they don’t want the Taliban to win, to go back to what it was before we were there. But there are civilians there that are like, “What are we going to do? A perpetual standoff? A conflict that’s never going to end?” And they’re just caught in the middle.

The personal aspects of the film where you can hear me, or where I’m asking questions, or where I’m filming in a certain way — we left that stuff in the film because of my responsibility and the role that I played and the guilt that I feel about it. I’ve been dealing with it by making this movie.

I want there to be some accountability. I don’t want people just to look at the soldiers and Marines as hapless victims that were sent out there, and it was just the big politicians that are responsible. No. I think the soldiers are responsible, the politicians are responsible, but also the American people are complicit. Our tax money funded the war. It’s not just the soldiers and the politicians. It’s the everyday citizens. We’re all responsible because we didn’t really give a shit. We didn’t notice it. We didn’t pay attention.